SAVING LIVES

PAD Trial Results Make the Case for Training Volunteers to Use AEDs

November 17, 2003Jacobowitz helps revive man at Whitestown meeting

December 4, 2003Six dramatic rescues (and counting) are credited to the union-backed defibrillator law

December 3, 2003

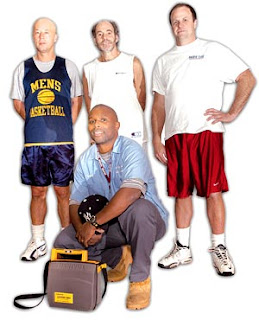

From left, teacher Charlie Bateman, dentist Alan Katz, and publisher Lee Minetree were part of the rescue team for Dexter Grady, shown in foreground with an AED.

When custodian Dexter Grady of East Hampton Middle School was trained last December to use the school’s new portable defibrillator, he never dreamed he’d be the first one revived by the life-saving device his union had helped to put in schools.

It was March 13. As usual on Tuesday and Thursday evenings, the 37-year-old custodian spent his dinner break playing a pickup game of basketball in the gym with a bunch of friends, including teachers Claude Beudert and Charlie Bateman.

Grady had just finished a game and was taking a breather when he suddenly felt light-headed and collapsed on the bleachers. Alan Katz, an East Hampton dentist, rushed over and began administering CPR, while Beudert and Bateman called for help and retrieved the Automated External Defibrillator from the hallway outside the gym. After three shocks with the AED, Grady started breathing normally and regained consciousness. He was rushed to a nearby hospital where he received bypass surgery.

“I’m here because of God’s grace and mercy, the quick actions of my buddies – and the fact that AEDs are required in every school,” said Grady, a member of the East Hampton Non-Teaching Employees in Suffolk County on Long Island.

In the nick of time

New York State United Teachers, his local union’s statewide affiliate, had helped achieve legislation just months before that required the life-saving devices be available in schools.

“We knew the law would save lives, but we had no idea how soon, or how many,” said NYSUT President Tom Hobart.

In addition to Grady, at least five other lives so far have been saved because AEDs were at school sites. “Hopefully these latest incidents will convince more school districts to come into compliance,” said NYSUT Executive Vice President Alan Lubin. “We are proud to have helped achieve legislation that has already had such a powerful impact for good.”

A grateful Grady returned to work. He is even back on the court, playing pickup basketball.

“If I had been somewhere else in the deep of the building, I would’ve been found dead,” Grady said. “Or if it had happened a few months earlier, or my district ignored the law, I’d be dead. There’s no question in my mind: That law saved my life.”

The union-backed bill, which requires an AED in every public school, was approved last year by the Legislature and governor after vigorous lobbying by the union and the passionate pleas of the parents of two teenage boys who died at school events where there was no defibrillator on hand.

Louis Acompora, 14, died March 2000, after he was struck in the chest while playing goalie for the Northport varsity lacrosse team. Gregory Moyer, 15, died in December 2000, while playing in a basketball game. Since their tragic deaths, the boys’ parents have made it their mission to turn grief into action – to get AEDs in public buildings around the state.

“This is Louis’ legacy,” said his mom, Karen Acompora, whose foundation donated the AED that saved Grady’s life. “When we lost Louis, we knew that we had do everything we could to prevent it from happening again.”

“Each AED in a public place is like lighting another candle for Gregory,” said Rachel Moyer, a Port Jervis teacher who worked with NYSUT, her statewide union, to win the law after she lost her son. “All these lives saved dramatically make the point that AEDs really do make a difference.”

An international scientific study released last month confirmed that survival chances from cardiac arrest are doubled if you’re helped by trained people using an AED.

In New York, in addition to Grady, other lives saved by school AEDs include:

- Dec. 9, 2001: Muhammad Shah of Nesconset, a 15-year-old student at Smithtown High, collapsed walking to class and was revived by school nurses Marilyn Clark and Liz Chitkara.

- Nov. 16, 2002: John Tierney, a 62-year-old football fan who collapsed in the stands at a high school playoff game was saved by an AED operated by Locust Valley athletic trainer Whittney Smith.

- Dec. 16, 2002: Andrea LaFleur, a 16-year-old automotive student at Orange-Ulster BOCES, was saved by teachers and a school nurse.

- Jan. 11, 2003: Judy Schneider, a 43-year-old chemistry professor at SUNY Oswego, was saved at Webster High School, where her daughter was competing in a swim meet.

In an amazing development last spring, NYSUT brought a defibrillator (donated as a “thank you” by the Moyers’ foundation) to its annual convention in Washington, D.C., where it was used to save the life of a New York City delegate in cardiac arrest. Retired Brooklyn district representative Herb Yules was rescued by a team led by nurses who are members of the United Federation of Teachers. Yules is now doing great and a big fan of AEDs.

Despite all the heartwarming stories, Rachel Moyer and Karen Acompora can’t stop thinking about the places that still don’t have AEDs.

During one tragic week in January 2003, three students from different New York City schools suddenly collapsed in cardiac arrest. One was in a classroom; another in a gym class; a third was trying out for baseball. The schools did not have AEDs: All three students died.

“We’re making progress, but we’re not where we should be,” Moyer said. “Too many schools are not in compliance. I have a list of 18 kids in the country who have died playing sports since Aug. 22, 2003, in schools.”

Moyer noted that in Orange County, athletic directors have agreed that sporting events will only be played at schools equipped with AEDs.

“I think that’s a great policy,” she said.

Moyer filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the State Education Department to find out how many New York schools are not in compliance with the state law that requires districts to purchase AEDs and train staff.

She was sent a list showing 638 districts out of 800 reported having at least one AED, but that means thousands of buildings still don’t have the life-saving device and trained staff.

“Just New York City has 1,200 buildings,” Moyer said.

School districts can pursue several avenues to secure funding for AEDs. Some schools and local unions have hosted fund-raising events; others have received state legislative grants or help from the Moyer and Acompora family foundations. With quantity discounts, the cost of the life-saving devices is down to about $2,000 each.

Survivors speak out

Perhaps the greatest advocates for AEDs are those who have been saved.

“I know I wouldn’t be here now if it weren’t for that defibrillator,” said Andrea LaFleur, who was saved by three teachers and a school nurse at Orange-Ulster BOCES. “I’m incredibly lucky that the (BOCES) Vo-Tech administrators responded so quickly to the new law and took the time to train people on how to use them.”

LaFleur was one of 42 survivors recognized recently in Washington by the National Center for Early Defibrillation, with 42 representing the number of people who suffer cardiac arrest every hour in the United States.

As part of the event, LaFleur spoke at a congressional briefing about the benefits of having high school students get AED and CPR training in health class.

Campus crusader

Another of the 42 survivor honorees was Judy Schneider, the chemistry professor at SUNY Oswego and a member of United University Professions. She was saved by lifeguards when she collapsed at her 10-year-old daughter’s swim meet at Webster High School.

“I’m living proof that everyone’s at risk – it could happen to anyone at anytime,” Schneider told congressional representatives and staff. “I was only 43 and had no previous heart problems, no blockage, no warning. It was just my good fortune that my heart short-circuited at a school that had an AED.”

Schneider, who now has an internal defibrillator pacemaker to keep her heart in check, urged congressional representatives to improve Medicare and Medicaid insurance plans to cover people who need the devices. “I’m blessed with good health insurance so it was covered; others aren’t so lucky.”

Schneider is working to get AEDs installed in every building on her sprawling campus. “I’ve been hunting for them on campus and found four,” Schneider said. “But if people don’t know where they are or how to use them, what good are they?”

Someday, Schneider would like to see AEDs as prevalent as fire extinguishers. “To me, they’re just as essential,” Schneider said. “Your life shouldn’t have to depend on where you happen to have a cardiac arrest.”

– Sylvia Saunders

NYSUT.org. Copyright New York State United Teachers. 800 Troy-Schenectady Road, Latham, New York, 12110-2455. 518.213.6000. http://www.nysut.org.