Broken Hearts Stopping the killer of young athletes

School staff help save co-worker’s life

November 28, 2012Teaming up to save a life

April 10, 2013P.K. Daniel November 29, 2012

On the morning of Saturday, April 19, 2008, the lacrosse field at Cardinal Gibbons High School in Raleigh, N.C., was awash in sunshine, a perfect day for a game. The stands were teeming with spectators, including many parents of players from the Providence Day School who had traveled three hours from Charlotte to watch their sons play.

Alex Beuris was a decorated high school All-American lacrosse player for the Crusaders of Cardinal Gibbons. Although he didn’t have huge dreams or expectations about playing in college, the events that occurred on that day derailed any notion of playing at the next level.

Beuris remembers driving to school that day. He even remembers where he parked. He recalls being late for the pregame meeting. But he doesn’t remember most of the game or the incident that almost ended his life. His last memory is running with some of his teammates through the halls of the school, trying to get to that meeting. After that, it’s just bits and pieces.

He doesn’t remember most of the game or the incident that almost ended his life.

The Crusaders’ senior co-captain, the team’s best defender, lined up opposite Providence Day’s best player, Kevin Sherrill. With the Crusaders leading the Chargers 5-3 early in the fourth quarter, Providence Day went on the attack. As the Chargers closed in on the Cardinal Gibbons’ goal on the south end of the field, Beuris prepared to check his opponent when Sherrill took a shot. The wayward shot on goal collided with Beuris’ chest. On impact the solid rubber lacrosse ball, weighing just over five ounces and no bigger than a tennis ball, became a potentially deadly weapon.

Beuris, stunned, staggered a few steps as he ripped off his helmet. Then he dropped to a sitting position before falling backward to the turf. As his body started violently convulsing, teammate Rory O’Brien was the first to reach him. O’Brien urgently waved to his father in the stands to come down to the field. Dr. Patrick O’Brien immediately raced onto the field.

Beuris, stunned, staggered a few steps as he ripped off his helmet. Then he dropped to a sitting position before falling backward to the turf. As his body started violently convulsing, teammate Rory O’Brien was the first to reach him. O’Brien urgently waved to his father in the stands to come down to the field. Dr. Patrick O’Brien immediately raced onto the field.

Photo of Alex Beuris (left) and Kevin Sherrill moments before Sherrill’s shot struck Beuris in the chest, causing an episode of commotio cordis, resulting in Sudden Cardiac Arrest, an event that nearly killed him.

Photo of Alex Beuris (left) and Kevin Sherrill moments before Sherrill’s shot struck Beuris in the chest, causing an episode of commotio cordis, resulting in Sudden Cardiac Arrest, an event that nearly killed him.The seizure ended, but Beuris had no pulse. His heart was quivering haphazardly, but had stopped pumping blood. This otherwise healthy 17-year-old athlete was experiencing commotio cordis—commotion of the heart. When the lacrosse ball struck his chest it disrupted his heart’s usual steady rhythm and caused sudden cardiac arrest (SCA).

Sudden cardiac arrest is the leading cause of death in young athletes, and the leading cause of SCA is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy – an inherited heart defect that causes abnormal thickening of the heart. But commotio cordis is the second-leading cause of SCA. The mean age of those afflicted is 15, and 95 percent of the victims have been male. It is not clear precisely why athletic boys are more susceptible than girls other than some physiological differences, such as having less fat under the skin to protect the heart behind chest walls that are still pliable and under-developed in many adolescent boys. In adult males, whose ribcages are fully developed and no longer as pliable, commotio cordis is much less of a risk.

More than 250 cases of commotio cordis have been recorded since the United States Commotio Cordis Registry, managed by the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation in Minneapolis, was formed in 1998. According to the registry, nearly half of 224 reported fatalities between 1996 and 2010 occurred in competitive sports. Recreational, backyard or playground sports account for a quarter of the cases while the remaining cases are attributable to events such as auto accidents or violent assault. There has been a recent increase in registry cases due to increased awareness, but experts still suspect the syndrome is under-reported and that the actual number of deaths might be much higher.

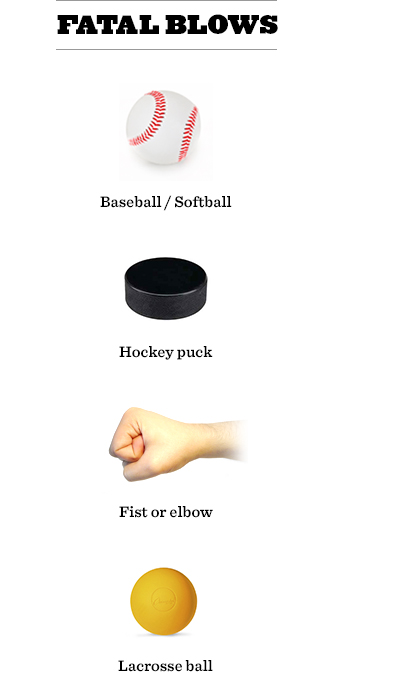

Commotio cordis occurs from a blow to the chest by a blunt object such as a baseball, hockey puck or lacrosse ball precisely at the 10-30 millisecond frame of the heart beat cycle – the upstroke of the T-wave, directly over the left ventricle of the heart. The impact interrupts the heart’s electrical impulses and it sends the heart into a chaotic rhythm. The blood stops flowing, resulting in insufficient blood flow to the brain. When that happened to Beuris, he lapsed into unconsciousness.

An October 2012 study in Heart Rhythm journal states that if resuscitation by CPR and the use of an automated external defibrillator (AED) takes place within three minutes of the event, the victim has a 40 percent chance of survival. An AED is a portable, automated device that checks the heart rhythm and provides a lifesaving shock, if necessary, to correct ventricular fibrillation and restore the heart to a normal rhythm. The device provides voice and text prompts, instructing even an untrained operator where to place the pads and when to apply the shock. After three minutes, however, the survival rate drops to only five percent. For Alex Beuris, every second mattered.

Sudden cardiac arrest is the leading cause of death in young athletes, and the leading cause of SCA is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy – an inherited heart defect that causes abnormal thickening of the heart. But commotio cordis is the second-leading cause of SCA. The mean age of those afflicted is 15, and 95 percent of the victims have been male. It is not clear precisely why athletic boys are more susceptible than girls other than some physiological differences, such as having less fat under the skin to protect the heart behind chest walls that are still pliable and under-developed in many adolescent boys. In adult males, whose ribcages are fully developed and no longer as pliable, commotio cordis is much less of a risk.

More than 250 cases of commotio cordis have been recorded since the United States Commotio Cordis Registry, managed by the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation in Minneapolis, was formed in 1998. According to the registry, nearly half of 224 reported fatalities between 1996 and 2010 occurred in competitive sports. Recreational, backyard or playground sports account for a quarter of the cases while the remaining cases are attributable to events such as auto accidents or violent assault. There has been a recent increase in registry cases due to increased awareness, but experts still suspect the syndrome is under-reported and that the actual number of deaths might be much higher.

Commotio cordis occurs from a blow to the chest by a blunt object such as a baseball, hockey puck or lacrosse ball precisely at the 10-30 millisecond frame of the heart beat cycle – the upstroke of the T-wave, directly over the left ventricle of the heart. The impact interrupts the heart’s electrical impulses and it sends the heart into a chaotic rhythm. The blood stops flowing, resulting in insufficient blood flow to the brain. When that happened to Beuris, he lapsed into unconsciousness.

An October 2012 study in Heart Rhythm journal states that if resuscitation by CPR and the use of an automated external defibrillator (AED) takes place within three minutes of the event, the victim has a 40 percent chance of survival. An AED is a portable, automated device that checks the heart rhythm and provides a lifesaving shock, if necessary, to correct ventricular fibrillation and restore the heart to a normal rhythm. The device provides voice and text prompts, instructing even an untrained operator where to place the pads and when to apply the shock. After three minutes, however, the survival rate drops to only five percent. For Alex Beuris, every second mattered.

Athletes playing baseball experience the highest number of incidents of commotio cortis per year, followed by softball, hockey, football and lacrosse, including the death of 12-year-old Tyler Kopp in upstate New York earlier this year. In that incident it was reported that an AED wasn’t applied to Kopp until after ambulance personnel arrived.

Just 51 days before Beuris was struck down, and 450 miles away in Jacksonville, Fla., another athletic, healthy young man was also felled by a lacrosse ball. James Hendrick was guarding the Fletcher High School goal on Feb. 27, 2008, when a shot soared toward him. Once again the hard rubber sphere proved to be a potentially deadly weapon.

The 16-year-old sophomore, encased in a goalie’s chest protector, stopped the ball with his chest. Like Beuris, he didn’t immediately drop to the ground. In fact, Hendrick shoveled the ball to midfielder Marcus Nelson before slumping to the turf. He, too, had suffered commotio cordis.

“When I got to James he was still breathing and looking at me,” said Fletcher coach Josh Covelli, who is also a firefighter and paramedic. “The first thought I had when I saw James was that he got hit in the throat and was hyperventilating, not that he took a ball to the chest and was going into cardiac arrest.”

Significantly, the chest protector he wore did not protect him from commotio cordis. Thomas Adams was an all-star catcher for his New Jersey travel baseball team. The 16-year-old Garfield High School sophomore died from commotio cordis after being struck in the chest by a pitch in 2010. He was wearing a catcher’s chest protector, but an AED was not available. According to The American Journal of Cardiology, almost 40 percent of commotio cordis deaths in young competitive athletes occurred while wearing chest barriers, devices that provide a measure of safety from a variety of injuries, including bone and soft tissue, but not –- as many parents, coaches and athletes believe – protection from commotio cordis.

Just 51 days before Beuris was struck down, and 450 miles away in Jacksonville, Fla., another athletic, healthy young man was also felled by a lacrosse ball. James Hendrick was guarding the Fletcher High School goal on Feb. 27, 2008, when a shot soared toward him. Once again the hard rubber sphere proved to be a potentially deadly weapon.

The 16-year-old sophomore, encased in a goalie’s chest protector, stopped the ball with his chest. Like Beuris, he didn’t immediately drop to the ground. In fact, Hendrick shoveled the ball to midfielder Marcus Nelson before slumping to the turf. He, too, had suffered commotio cordis.

“When I got to James he was still breathing and looking at me,” said Fletcher coach Josh Covelli, who is also a firefighter and paramedic. “The first thought I had when I saw James was that he got hit in the throat and was hyperventilating, not that he took a ball to the chest and was going into cardiac arrest.”

Significantly, the chest protector he wore did not protect him from commotio cordis. Thomas Adams was an all-star catcher for his New Jersey travel baseball team. The 16-year-old Garfield High School sophomore died from commotio cordis after being struck in the chest by a pitch in 2010. He was wearing a catcher’s chest protector, but an AED was not available. According to The American Journal of Cardiology, almost 40 percent of commotio cordis deaths in young competitive athletes occurred while wearing chest barriers, devices that provide a measure of safety from a variety of injuries, including bone and soft tissue, but not –- as many parents, coaches and athletes believe – protection from commotio cordis.

Automated external defibrillator, AED. Source

Automated external defibrillator, AED. SourceWith the intervention of immediate medical assistance, including an AED, athletes can survive this often-fatal and hard-to-recognize event. The Commotio Cordis Registry indicates mortality rates have decreased over the past four decades. About 15 years ago, survivability was around 15 percent. Today, it is about 50 percent. This is likely due to quicker response times, increased access to defibrillation and a greater awareness of commotio cordis.

“No doubt about it, the mortality rate for commotio cordis has gone down,” said Dr. Barry Maron of the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation. He attributes it to “education, visibility and AEDS. [And] the awareness of commotio cordis – that it’s a lethal event.”

When Hendrick was injured, his coach didn’t immediately bring the AED with him that was resting on the sideline. “We were talking to him, trying to figure out what happened,” said Covelli. Hendrick’s breathing was rapid. He responded to commands with grunts. “Then all of the sudden, his skin colored changed. It went from flush and normal to pale and white. I knew something else was going on at that point.”

Someone called 911. CPR was started. The AED was grabbed and the pads were attached to his chest. Hendrick was successfully revived before a helicopter landed on the high school field to transport him to the local hospital. Three weeks later he returned to the lacrosse field.

“He had no down time,” said Covelli. “He had absolutely no deficit to his brain or heart. Unfortunately, that’s not the case with everybody.”

“No doubt about it, the mortality rate for commotio cordis has gone down,” said Dr. Barry Maron of the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation. He attributes it to “education, visibility and AEDS. [And] the awareness of commotio cordis – that it’s a lethal event.”

When Hendrick was injured, his coach didn’t immediately bring the AED with him that was resting on the sideline. “We were talking to him, trying to figure out what happened,” said Covelli. Hendrick’s breathing was rapid. He responded to commands with grunts. “Then all of the sudden, his skin colored changed. It went from flush and normal to pale and white. I knew something else was going on at that point.”

Someone called 911. CPR was started. The AED was grabbed and the pads were attached to his chest. Hendrick was successfully revived before a helicopter landed on the high school field to transport him to the local hospital. Three weeks later he returned to the lacrosse field.

“He had no down time,” said Covelli. “He had absolutely no deficit to his brain or heart. Unfortunately, that’s not the case with everybody.”

Even the product names prey on parents’ fears.

Given these risks, parents may want to bubble wrap their susceptible athletic boys thinking this will protect them against commotio cordis. But counter to that logic, there are no chest protectors on the market, some of which come imbedded in special shirts to hold them in place while others are sold as separate, insertable guards, that are proven to prevent commotio cordis. Using juvenile swine, the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment (NOCSAE) has tested many chest protectors on the market and found them ineffective. And yet manufacturers make wildly misleading promises and unsubstantiated claims of performance. Even the product names – XO HeartShield, Safe-Heart, Heart-Gard, EvoShield, Safe Than Sorry, etc. – prey on parents’ fears. Rather than rely on these unproven devices, parents, coaches and league administrators could be ensuring their youth and school sports teams are outfitted with AEDs and that emergency action plans are in place.

Heart-Gard, top seller of youth chest protectors.

Heart-Gard, top seller of youth chest protectors.The medical community is particularly critical of the Heart-Gard manufactured by Markwort Sporting Goods Company, reportedly the top seller of youth chest protectors. Markwort describes the product, featured on the front page of the company’s website, as “a tough, high density polyethylene dome that absorbs impact energy and forces it away from the heart.”

Dr. Maron thinks the Heart-Gard and other products of this type give parents a false sense of security. “I certainly think that Heart-Gard does,” he said. “It doesn’t cover the heart. Since we start with the known assumption that there isn’t anything out there right now that has been shown to be protective to obliterate this risk, the whole thing is just a ‘whatever makes you feel better.’

“But certainly spending money on a protector that promotes specifically for commotio cordis that doesn’t cover the heart would seem not to be ideal. As a physician, I don’t know how to recommend something that I know doesn’t work. I certainly wouldn’t buy Heart-Gard because it doesn’t even cover the heart. It was made by an engineer, who not only hasn’t been to medical school, he doesn’t care to know. But he does care to sell these things as a peace-of-mind thing.

“Bottom line is clear. None of them has been shown to be protective. There is no product.” As far as science is concerned, the protective devices marketed to provide protection from commotio cordis are no more effective than diet pills sold on late night infomercials or supplements like the acai berry that have bilked unsuspecting consumers out of hundreds of millions of dollars. Dr. Mark Link of the New England Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at the Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston echoed Dr. Maron’s opinion on Heart-Gard that makes the claim that it “helps reduce the possibility of injury or death.”

“They do not have any proof of this,” said Dr. Link. “In fact, in our experimental model they did not protect from commotio cordis. We have been working with Wayne State (University in Detroit, MI) engineers and NOCSAE to develop a standard to evaluate chest protector claims. Hopefully this mechanical model will be validated soon and put into use.”

None of these devices have been proven to be either safe or effective. Consumers can find chest protectors in most sporting goods stores and find multiple products for sale online. The packaging for the XO HeartShield reads: “Strong heart protection for boys and girls! Most effective and comfortable heart protection you can buy!” Safe-Heart co-founder Phil D’Amato says on the website for his product: “First and foremost, the shield protector portion may help to protect them from injury or death if they are hit in the heart/chest area. Furthermore, this product will provide peace of mind to parents and confidence to children since they’ll feel safer,” he said. “As far as we are concerned, this extra protection is better than no protection at all.”

But is it? Some chest protectors are known to have failed because they did not adequately cover the athlete’s chest and thus protect the cardiac silhouette. The Journal of the American College of Cardiology says “protective gear that portends to provide protection against sudden death due to chest wall impact during sports activities must cover the entire cardiac silhouette regardless of body movement or position.”

Dr. Maron thinks the Heart-Gard and other products of this type give parents a false sense of security. “I certainly think that Heart-Gard does,” he said. “It doesn’t cover the heart. Since we start with the known assumption that there isn’t anything out there right now that has been shown to be protective to obliterate this risk, the whole thing is just a ‘whatever makes you feel better.’

“But certainly spending money on a protector that promotes specifically for commotio cordis that doesn’t cover the heart would seem not to be ideal. As a physician, I don’t know how to recommend something that I know doesn’t work. I certainly wouldn’t buy Heart-Gard because it doesn’t even cover the heart. It was made by an engineer, who not only hasn’t been to medical school, he doesn’t care to know. But he does care to sell these things as a peace-of-mind thing.

“Bottom line is clear. None of them has been shown to be protective. There is no product.” As far as science is concerned, the protective devices marketed to provide protection from commotio cordis are no more effective than diet pills sold on late night infomercials or supplements like the acai berry that have bilked unsuspecting consumers out of hundreds of millions of dollars. Dr. Mark Link of the New England Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at the Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston echoed Dr. Maron’s opinion on Heart-Gard that makes the claim that it “helps reduce the possibility of injury or death.”

“They do not have any proof of this,” said Dr. Link. “In fact, in our experimental model they did not protect from commotio cordis. We have been working with Wayne State (University in Detroit, MI) engineers and NOCSAE to develop a standard to evaluate chest protector claims. Hopefully this mechanical model will be validated soon and put into use.”

None of these devices have been proven to be either safe or effective. Consumers can find chest protectors in most sporting goods stores and find multiple products for sale online. The packaging for the XO HeartShield reads: “Strong heart protection for boys and girls! Most effective and comfortable heart protection you can buy!” Safe-Heart co-founder Phil D’Amato says on the website for his product: “First and foremost, the shield protector portion may help to protect them from injury or death if they are hit in the heart/chest area. Furthermore, this product will provide peace of mind to parents and confidence to children since they’ll feel safer,” he said. “As far as we are concerned, this extra protection is better than no protection at all.”

But is it? Some chest protectors are known to have failed because they did not adequately cover the athlete’s chest and thus protect the cardiac silhouette. The Journal of the American College of Cardiology says “protective gear that portends to provide protection against sudden death due to chest wall impact during sports activities must cover the entire cardiac silhouette regardless of body movement or position.”

Model wearing the Heart-Gard product.

Model wearing the Heart-Gard product.That’s another way of saying there are products on the market whose design, like Heart-Gard, may not properly cover the heart. Many chest protectors include a rigid plate designed to spread the impact over a larger area. The photograph of the model wearing the shirt on the Markwort website clearly shows the Heart-Gard over the center of the upper body. The device covers the lower breast bone but appears to cover only a portion of the heart and may leave much of the organ exposed, a problem with many such devices. The problem is that if such protective plates are centered on the chest, the edge of the plate itself can be over the cardiac silhouette. According to Dr. Nathan Dau, Ph.D., a research associate with Legacy Research Institute, this not only leaves part of the heart exposed, but could result in a chest protector actually directing impact force toward the heart, which would increase the risk of commotio cordis. The product that is supposed to save an athlete’s life could possibly prove to be a killer, turning a benign blow into a potentially deadly one.

The fear, too, is that parents who buy into manufacturers’ claims and purchase an ineffective $30 or $40 chest protector don’t push for youth leagues and school athletic programs to acquire the more expensive AEDs, whose effectiveness and value is unquestioned. Despite the repeated reports dismissing the efficacy of current commercial chest protectors, after a child’s death concerned parents litter message boards advocating for their use while overlooking AEDS, whose beneficiaries could be anyone at a sporting event who suffers cardiac arrest.

“If a parent decides we don’t need to spend the money toward a defibrillator because we’re all wearing the Heart-Gard, well guess what? They have a false sense of security,” said Dr. Jeffrey Mandak, a cardiologist in Pennsylvania and a member of the U.S. Lacrosse Sports Science and Safety Committee. “That kind of advertising is so dangerous.”

Even more frightening is that doctors are not even certain whether a properly placed chest protector that reduces impact velocity provides protection. Some research has indicated that impacts at 40 mph were more likely to produce ventricular fibrillation than impacts of greater or lesser velocities. Some data also showed that chest protectors that decreased the force of impact could then theoretically increase the risk of commotio cordis into the danger velocity range. In other words, reducing impact speed could prove more dangerous. However, more recent research by Dr. Dau questions that finding. His analysis shows that as projectile speed increased, the risk of commotio cordis also increased, indicating there may not be a maximum velocity above which the risk of commotio cordis decreases.

“His research shows that wasn’t true, that it was more of a linear relationship that the higher level of force, the higher the risk of commotio cordis,” said Dr. Mandak. “It’s up for debate whether 40 [miles per hour] is the peak or whether it still continues to increase in risk as you go higher. The idea of peak velocity is a little nebulous right now given this new research. Bottom line is we don’t have a definitive answer.”

Dr. Maron also was not sold on the previous data that protectors that decreased the force of impact could theoretically put them in the danger velocity range.

“Well, that’s a theoretic argument,” said Dr. Maron. “I don’t know whether it’s true or not … It’s a hypothetical. I guess it could be a contributing factor. It’s a theoretic possibility. This is all unknown in the real world.”

“The only thing that matters,” he said,” is that there isn’t any chest protector that’s proven protective against [commotio cordis]. There’s no other way to look at it.”

However, even Dr. Link, who authored some of the previous research, is now of the mind-set that something is probably better than nothing. “I don’t think that chest protectors will increase risk,” he said. “I know that this argument has been made before, even by me, but I don’t believe that anymore.”

“That kind of advertising is so dangerous.”

The fear, too, is that parents who buy into manufacturers’ claims and purchase an ineffective $30 or $40 chest protector don’t push for youth leagues and school athletic programs to acquire the more expensive AEDs, whose effectiveness and value is unquestioned. Despite the repeated reports dismissing the efficacy of current commercial chest protectors, after a child’s death concerned parents litter message boards advocating for their use while overlooking AEDS, whose beneficiaries could be anyone at a sporting event who suffers cardiac arrest.

“If a parent decides we don’t need to spend the money toward a defibrillator because we’re all wearing the Heart-Gard, well guess what? They have a false sense of security,” said Dr. Jeffrey Mandak, a cardiologist in Pennsylvania and a member of the U.S. Lacrosse Sports Science and Safety Committee. “That kind of advertising is so dangerous.”

Even more frightening is that doctors are not even certain whether a properly placed chest protector that reduces impact velocity provides protection. Some research has indicated that impacts at 40 mph were more likely to produce ventricular fibrillation than impacts of greater or lesser velocities. Some data also showed that chest protectors that decreased the force of impact could then theoretically increase the risk of commotio cordis into the danger velocity range. In other words, reducing impact speed could prove more dangerous. However, more recent research by Dr. Dau questions that finding. His analysis shows that as projectile speed increased, the risk of commotio cordis also increased, indicating there may not be a maximum velocity above which the risk of commotio cordis decreases.

“His research shows that wasn’t true, that it was more of a linear relationship that the higher level of force, the higher the risk of commotio cordis,” said Dr. Mandak. “It’s up for debate whether 40 [miles per hour] is the peak or whether it still continues to increase in risk as you go higher. The idea of peak velocity is a little nebulous right now given this new research. Bottom line is we don’t have a definitive answer.”

Dr. Maron also was not sold on the previous data that protectors that decreased the force of impact could theoretically put them in the danger velocity range.

“Well, that’s a theoretic argument,” said Dr. Maron. “I don’t know whether it’s true or not … It’s a hypothetical. I guess it could be a contributing factor. It’s a theoretic possibility. This is all unknown in the real world.”

“The only thing that matters,” he said,” is that there isn’t any chest protector that’s proven protective against [commotio cordis]. There’s no other way to look at it.”

However, even Dr. Link, who authored some of the previous research, is now of the mind-set that something is probably better than nothing. “I don’t think that chest protectors will increase risk,” he said. “I know that this argument has been made before, even by me, but I don’t believe that anymore.”

Heart-Gard chest protector.

Heart-Gard chest protector.Still, the debate is ongoing and uncertainty is the rule. Mike Oliver, executive director of NOCSAE, has said baseball chest protectors could put young catchers in greater danger. He is hesitant to endorse Dr. Link’s broad statement.

“It does not take into account matters of design, construction and performance of all chest protectors in all sports,” said Oliver. “To say that no chest protector, regardless of its design, could increase the risk of commotio cordis assumes that no chest protector design exists or will exist that is shaped in such a way as to concentrate the impact energy over the cardiac silhouette. I hope that such would not be the case, but without a researched and tested performance standard, there is no way to know.

“Protecting against commotio cordis is more complex than simply having some padding in front of the impacting object. We know that a large number of commotio cordis events have occurred to players wearing some type of commercially available padded chest protector.” Dr. Mandak supported Oliver’s concern about the design of protectors that make the focal point on the cardiac silhouette instead of dispersing it.

“Some of the designs still increase the risk because they’re focusing the energy,” he said.

“Studies have shown that reduced diameter spheres increase the risk of commotio cordis,” said Dave Halstead, technical director of NOCSAE. “And while spreading the impact force over a larger area may decrease the risk of sudden death and has implications for the design of protective athletic equipment, despite claims to the contrary, so far there is no chest protector on the market that has shown it will reduce the risk.”

What everyone seems to agree on, however, is that there is no chest protector – none – proven to protect against commotio cordis.

“There is no evidence that any available chest protector system … or any other device on the market today is effective in the reduction of commotio cordis,” said Halstead. “It is hoped that there will be a standard test method and performance specifications for such devices in the near future. Until there is such a test, claims of injury reduction relative to commotio cordis should be viewed with great skepticism.”

Louis J. Acompora was 14 years old when he died from commotio cordis during his first high school lacrosse game in 2000. NOCSAE has joined the Louis J. Acompora Memorial Foundation in investing in research that it believes will lead to a standard for testing such devices.

“We are a bit closer to a NOCSAE test for such protectors,” said Halstead. “Human chest surrogates are being constructed, and I expect we will have a series of round-robin testing completed in the next year. If the devices are repeatable and have been validated against the animal model to the satisfaction of the scientific committee of NOCSAE, then the road is cleared for a standard.”

“It does not take into account matters of design, construction and performance of all chest protectors in all sports,” said Oliver. “To say that no chest protector, regardless of its design, could increase the risk of commotio cordis assumes that no chest protector design exists or will exist that is shaped in such a way as to concentrate the impact energy over the cardiac silhouette. I hope that such would not be the case, but without a researched and tested performance standard, there is no way to know.

“Protecting against commotio cordis is more complex than simply having some padding in front of the impacting object. We know that a large number of commotio cordis events have occurred to players wearing some type of commercially available padded chest protector.” Dr. Mandak supported Oliver’s concern about the design of protectors that make the focal point on the cardiac silhouette instead of dispersing it.

“Some of the designs still increase the risk because they’re focusing the energy,” he said.

“Studies have shown that reduced diameter spheres increase the risk of commotio cordis,” said Dave Halstead, technical director of NOCSAE. “And while spreading the impact force over a larger area may decrease the risk of sudden death and has implications for the design of protective athletic equipment, despite claims to the contrary, so far there is no chest protector on the market that has shown it will reduce the risk.”

What everyone seems to agree on, however, is that there is no chest protector – none – proven to protect against commotio cordis.

“There is no evidence that any available chest protector system … or any other device on the market today is effective in the reduction of commotio cordis,” said Halstead. “It is hoped that there will be a standard test method and performance specifications for such devices in the near future. Until there is such a test, claims of injury reduction relative to commotio cordis should be viewed with great skepticism.”

Louis J. Acompora was 14 years old when he died from commotio cordis during his first high school lacrosse game in 2000. NOCSAE has joined the Louis J. Acompora Memorial Foundation in investing in research that it believes will lead to a standard for testing such devices.

“We are a bit closer to a NOCSAE test for such protectors,” said Halstead. “Human chest surrogates are being constructed, and I expect we will have a series of round-robin testing completed in the next year. If the devices are repeatable and have been validated against the animal model to the satisfaction of the scientific committee of NOCSAE, then the road is cleared for a standard.”

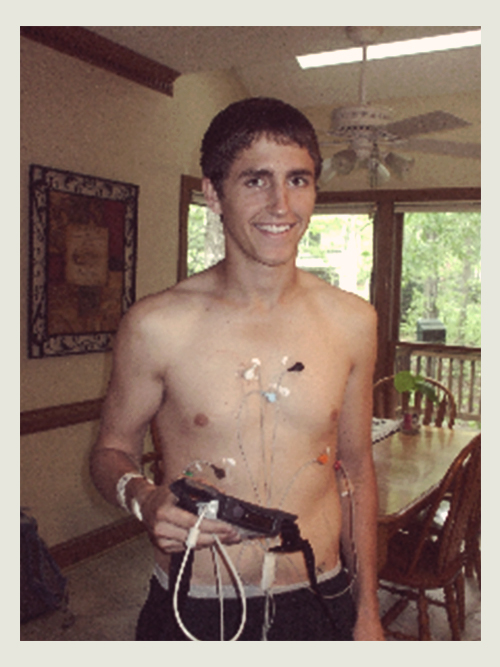

Alex Beuris wearing a precautionary heart monitor two days after the incident, on April 21, 2008.

Alex Beuris wearing a precautionary heart monitor two days after the incident, on April 21, 2008.But since the consensus is that no chest protector exists that’s been proven to reduce the risk, the best chance to survive commotio cordis is CPR, followed by the use of an AED within 3 minutes. The American Heart Association says AEDs cost between $1,500-$2,000, depending on make and model, a price which drops considerably when purchased in bulk. Typically, the battery is good for up to four years or up to 290 shocks.

In baseball and softball, catchers, infielders and batters attempting to bunt, appear to be the most vulnerable. Although experts recommend that lacrosse and hockey players should avoid using their chest to block a puck or ball and that youth baseball leagues use safety balls and teach batters to turn away from a pitch, no such measures can prevent accidents from taking place. When they do, an AED is often the difference between life and death. Last year, 13-year-old Hayden Walton, a Little League player from Winslow, Ariz., attempted to bunt and was hit in the chest. He dropped the bat and walked a couple of steps toward first base before falling to the ground. CPR was performed, but no AED was available. He died the next morning at the hospital.

In baseball and softball, catchers, infielders and batters attempting to bunt, appear to be the most vulnerable. Although experts recommend that lacrosse and hockey players should avoid using their chest to block a puck or ball and that youth baseball leagues use safety balls and teach batters to turn away from a pitch, no such measures can prevent accidents from taking place. When they do, an AED is often the difference between life and death. Last year, 13-year-old Hayden Walton, a Little League player from Winslow, Ariz., attempted to bunt and was hit in the chest. He dropped the bat and walked a couple of steps toward first base before falling to the ground. CPR was performed, but no AED was available. He died the next morning at the hospital.

“They started to do mouth to mouth on him. I didn’t know if he was going to live.”

Alex Beuris wasn’t able to avoid the lacrosse ball that spring day, and he wasn’t wearing any chest protection. He survived because of an AED.

“By the time I got down to the field and got close to him he was literally blue,” said Alex’s mother, Sharon Beuris. “Ironically, the AED was not on the field that day. They started to do mouth to mouth on him. … I didn’t know if he was going to live.”

Beuris had made the varsity team as a freshman. As the youngest member of the team, it was his job that year to make sure the AED device got to the field – home and away – a responsibility that had been passed down to others over the years. Normally, the AED would have been on the sideline. But because this game was being played on a Saturday the AED was tucked away inside the gymnasium, about a hundred feet away.

Beuris’ teammate Jared Donabedian raced to retrieve the AED, but the gym was locked. He ran back to the field and notified Cardinal Gibbons coach Mike Curatolo , and Curatolo, in a full sprint and keys in hand, returned to the gym.

Meanwhile, back on the field, Alex’s jersey was being cut away. Dr. O’Brien started chest compressions. He was joined by Dr. Eric Laxer, a parent from the other team, who started mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Someone else held Alex’s ankles up around their neck trying to get the blood flow to his head.

What was about a one-minute wait for the AED seemed like forever to Alex’s mother, Sharon. “I saw the image of (Alex’s) mom sobbing on the ground as they’re putting the defibrillation on him,” said Curatolo.

Alex didn’t respond to the first shock. His heart started beating again with the second shock.

A shaken Curatolo, who stood watch as his player was being treated, surveyed the situation in front of him as members of both teams gathered before Alex was carted off to the waiting ambulance.

“You’re like ‘What the heck just happened?’ And not having any real good answers at the point, it was a very difficult moment, very tenuous,” said Curatolo.

The AED unquestionably saved Beuris’ life, but the incident had a lasting impact on him. A week after the incident, Beuris attended a pre-prom dinner with his girlfriend, but decided he wasn’t up for the dance afterward. Beuris suffered from short-term memory issues and extreme fatigue for days after – something not typical of a conditioned athlete.

In the months to follow he underwent a variety of medical tests – cardiological and neuropsychological. There was some concern whether Beuris was going to be ready to start college in the fall. “May was a really tough month because they weren’t sure how long this was going to last, or if he was going to recover fully,” said Curatolo. “It was a really scary time. Most of the cases I’ve heard about are not the ones who live, but the ones who die.”

“By the time I got down to the field and got close to him he was literally blue,” said Alex’s mother, Sharon Beuris. “Ironically, the AED was not on the field that day. They started to do mouth to mouth on him. … I didn’t know if he was going to live.”

Beuris had made the varsity team as a freshman. As the youngest member of the team, it was his job that year to make sure the AED device got to the field – home and away – a responsibility that had been passed down to others over the years. Normally, the AED would have been on the sideline. But because this game was being played on a Saturday the AED was tucked away inside the gymnasium, about a hundred feet away.

Beuris’ teammate Jared Donabedian raced to retrieve the AED, but the gym was locked. He ran back to the field and notified Cardinal Gibbons coach Mike Curatolo , and Curatolo, in a full sprint and keys in hand, returned to the gym.

Meanwhile, back on the field, Alex’s jersey was being cut away. Dr. O’Brien started chest compressions. He was joined by Dr. Eric Laxer, a parent from the other team, who started mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Someone else held Alex’s ankles up around their neck trying to get the blood flow to his head.

What was about a one-minute wait for the AED seemed like forever to Alex’s mother, Sharon. “I saw the image of (Alex’s) mom sobbing on the ground as they’re putting the defibrillation on him,” said Curatolo.

Alex didn’t respond to the first shock. His heart started beating again with the second shock.

A shaken Curatolo, who stood watch as his player was being treated, surveyed the situation in front of him as members of both teams gathered before Alex was carted off to the waiting ambulance.

“You’re like ‘What the heck just happened?’ And not having any real good answers at the point, it was a very difficult moment, very tenuous,” said Curatolo.

The AED unquestionably saved Beuris’ life, but the incident had a lasting impact on him. A week after the incident, Beuris attended a pre-prom dinner with his girlfriend, but decided he wasn’t up for the dance afterward. Beuris suffered from short-term memory issues and extreme fatigue for days after – something not typical of a conditioned athlete.

In the months to follow he underwent a variety of medical tests – cardiological and neuropsychological. There was some concern whether Beuris was going to be ready to start college in the fall. “May was a really tough month because they weren’t sure how long this was going to last, or if he was going to recover fully,” said Curatolo. “It was a really scary time. Most of the cases I’ve heard about are not the ones who live, but the ones who die.”

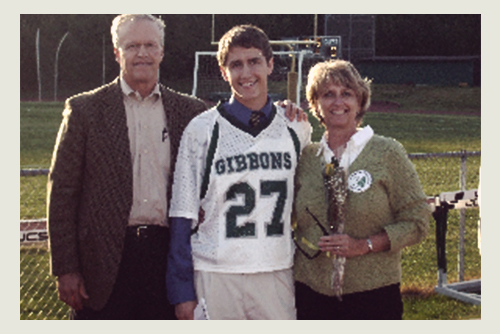

Beuris with his parents on Senior Night, April 29, 2008.

Beuris with his parents on Senior Night, April 29, 2008.Beuris was able to start the fall semester on time, but he initially utilized disability services at UNC, which provided him with a note-taker, a private room to take exams and more time to complete them. By the end of his fall term of his freshman year, Beuris made a full recovery and no longer required the services.

“I felt normal,” he said. “For me to be getting special treatment didn’t feel right. I didn’t really want it.”

Beuris thought about walking on to the lacrosse team at North Carolina. With a new coach overseeing the program he decided not to, but the political science major is scheduled to graduate Dec. 8. That, in and of itself, is pretty remarkable considering four and a half years earlier, he was lying unconscious on his high school lacrosse field, on the precipice of death.

“It’s definitely impacted me,” said Beuris. “I appreciate every day I have. If things aren’t going so well at least I’m around to experience them as opposed to the (alternative). . . I have a lot to be thankful for.”

It affected his mom, too. “You look at things a little differently,” said Sharon Beuris. “You try to live life and appreciate the positive things in life.”

Beuris doesn’t remember the incident that almost ended his life. He has a vague recollection of coming to in the ambulance, where his assistant coach John Wasco had accompanied him.

“There were a bunch of voices,” recall Beuris. “My assistant coach was in the ambulance and I remember his voice: ‘What’s your name? Where are you from? How old are you? When do you graduate?’

Then Beuris was asked who the president was.

“Fuckin’ Bush,” he said. Wasco replied: “He’s back.” ★

“I felt normal,” he said. “For me to be getting special treatment didn’t feel right. I didn’t really want it.”

Beuris thought about walking on to the lacrosse team at North Carolina. With a new coach overseeing the program he decided not to, but the political science major is scheduled to graduate Dec. 8. That, in and of itself, is pretty remarkable considering four and a half years earlier, he was lying unconscious on his high school lacrosse field, on the precipice of death.

“I appreciate every day I have.”

“It’s definitely impacted me,” said Beuris. “I appreciate every day I have. If things aren’t going so well at least I’m around to experience them as opposed to the (alternative). . . I have a lot to be thankful for.”

It affected his mom, too. “You look at things a little differently,” said Sharon Beuris. “You try to live life and appreciate the positive things in life.”

Beuris doesn’t remember the incident that almost ended his life. He has a vague recollection of coming to in the ambulance, where his assistant coach John Wasco had accompanied him.

“There were a bunch of voices,” recall Beuris. “My assistant coach was in the ambulance and I remember his voice: ‘What’s your name? Where are you from? How old are you? When do you graduate?’

Then Beuris was asked who the president was.

“Fuckin’ Bush,” he said. Wasco replied: “He’s back.” ★